Colchicine Guards Heart While Fighting Gout Flares

Introduction

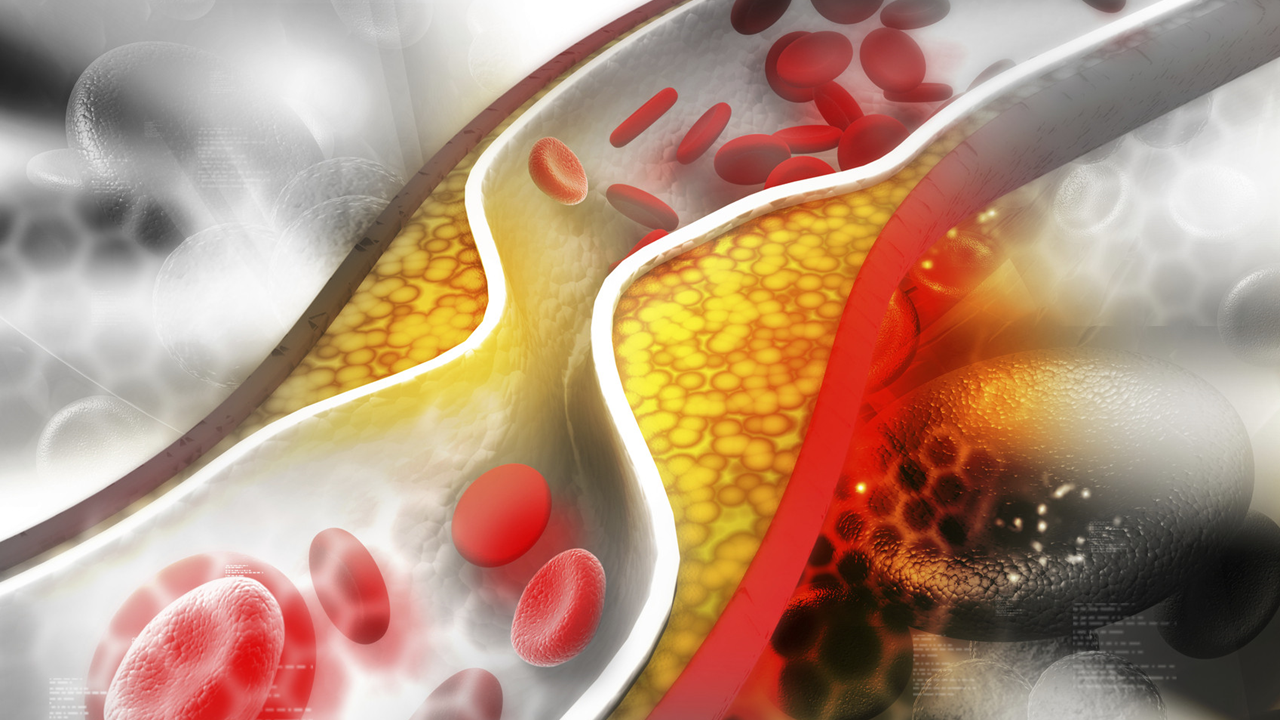

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis worldwide and affects 2·5%–5·0% of adults in high-income countries. It occurs due to sustained hyperuricaemia that causes monosodium urate crystals to deposit in and around joints. The release of crystals from pre-formed deposits causes intense inflammatory flares of joint pain and swelling that last for approximately 1–2 weeks.

Gout can be effectively managed with long-term urate-lowering therapy, with cessation of gout flares, provided a serum urate concentration of 360 μmol/L or less (≤300 μmol/L in those with tophi) is reached and maintained long-term. However, reduction in serum urate within the first few months of starting urate-lowering therapy can trigger gout flares as the solubilisation and subsequent shedding of monosodium urate crystals can initiate inflammation resulting in flares.4 Consequently, flare prophylaxis, with colchicine as a first-line drug, is recommended during the first 3–6 months of urate-lowering therapy. However, only 10–20% of people with gout are prescribed gout flare prophylaxis.

Methodology

Retrospective cohort study of 99,800 patients (mean age, 62.8 years; 74.4% men; 85.1% White) newly diagnosed with gout between January 1997 and March 2021 who initiated urate-lowering therapy.

Gout flare prophylaxis, defined as a colchicine prescription for 21 days or more, was prescribed to 16,028 patients for a mean duration of 47.3 days at a mean daily dose of 0.97 mg.

Patients who received colchicine prophylaxis and 83,772 patients who did not receive prophylaxis were followed for a mean of 175.5 and 176.9 days, respectively, in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The primary outcome was the occurrence of the first cardiovascular event (fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke) within 180 days of initiation of urate-lowering therapy.

Takeaway

The risk for cardiovascular events was significantly lower with colchicine prophylaxis than without it (weighted hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.94).

The risk for a first-ever cardiovascular event was significantly lower with colchicine prophylaxis than without it (adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.62-0.97).

The findings were similar regardless of analytical approach, and the intention-to-treat analysis did not show an increased risk for diarrhea with colchicine.

In practice

“The findings support consideration for the use of colchicine in people with gout and cardiovascular diseases,” the authors wrote.

“The observed beneficial effect of colchicine concerns a huge group of patients worldwide. In addition, it is conceivable that, if a cardiovascular risk reduction is indeed confirmed, a strong argument arises to recommend the prescription of a course of colchicine to all [flaring] patients with gout, independently of their preference for urate-lowering therapy in general or urate-lowering therapy with or without colchicine prophylaxis more specifically,” experts wrote in a linked commentary.

Conclusion

In patients with gout initiating urate-lowering therapy, gout flare prophylaxis with colchicine was associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular events for up to the next 180 days compared with no prophylaxis. These findings provide an additional argument for using gout flare prophylaxis when starting urate-lowering therapy. In countries in which colchicine is licenced for cardiovascular disease prevention, the findings of our study and previously published studies support consideration for the use of colchicine in people with gout and cardiovascular diseases. These findings could be confirmed in an adequately powered randomised controlled trial. However, such a trial would be practically prohibitive because withholding colchicine flare prophylaxis from people starting urate-lowering therapy as is recommended in rheumatology clinical practice guidelines is unethical, even though there is limited supporting evidence.

Limitations

Because of the retrospective nature of the data extraction from a prospective database, the study had variations in follow-up and data completeness. Potential surveillance bias could have been introduced because patients with prior cardiovascular events were included in the study, and patients’ adherence to prescribed medications could not be verified.

Disclosures

This study was funded by the Foundation for Research in Rheumatology. Some authors reported receiving consulting fees, lecturing fees, and travel grants from various pharmaceutical companies and other additional sources.

Source

Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, Academic Rheumatology, School of Medicine, Nottingham City Hospital, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, led the study, which was published online on December 18, 2024, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Bài viết liên quan