Is This the Tipping Point to Slash Salt in Our Diet

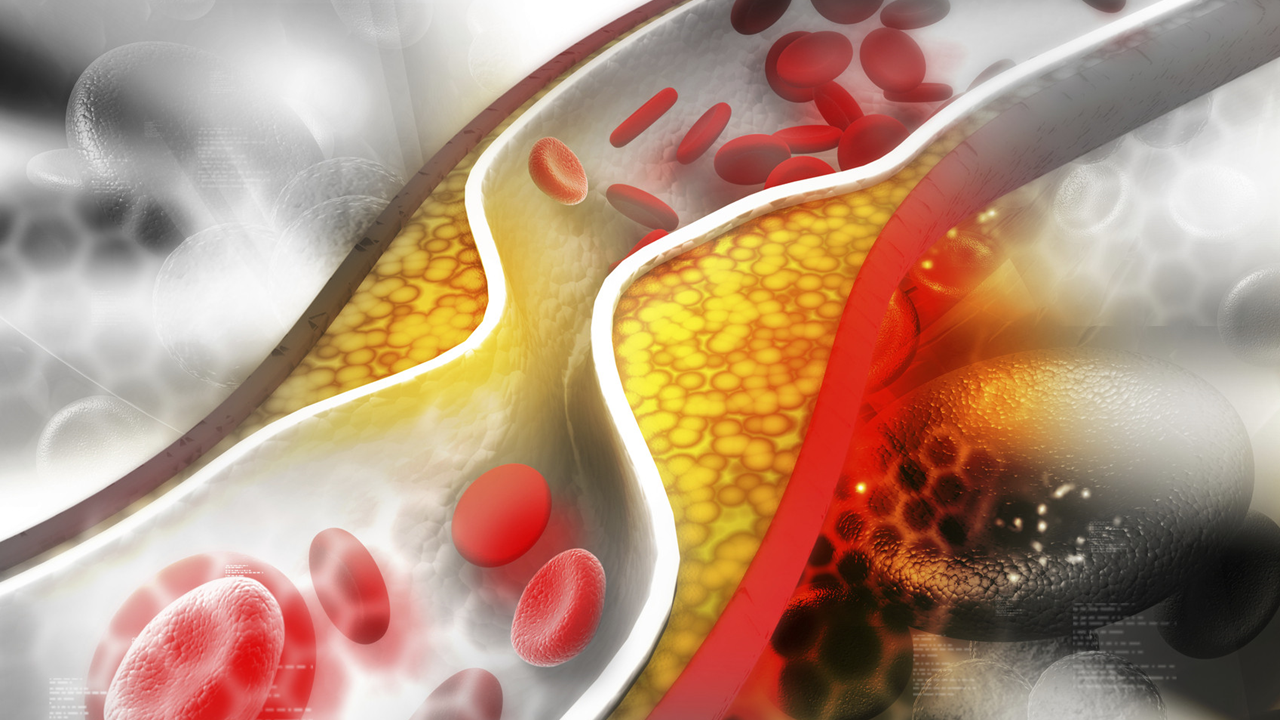

A teaspoon of salt is the recommended daily sodium intake according to US dietary guidelines, yet many people consume far more. The understanding of salt's impact on cardiovascular health has evolved from observational studies to clinical trials, culminating in new research that may represent a turning point in sodium regulation.

A recent study, a subset of the Salt Substitute and Stroke Study, investigated the effects of a salt alternative containing 25% potassium on stroke and death rates

Striking Double-Digit Percentage Improvements

With a 14% reduction in stroke and 12% decrease in death, "The simple intervention of salt substitution could significantly improve secondary prevention of stroke and cardiovascular health on a global scale," the investigators reported in JAMA Cardiology on February 5.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says that table salt is not the biggest problem, and 70% of dietary sodium comes from eating packaged and prepared foods. The agency says it is working with the food industry "to make reasonable reductions in sodium across a wide variety of foods."

In an article accompanying the new trial result, editorialists led by Daniel W. Jones, MD, with the Department of Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi, call this "the tipping point" for evidence that lower sodium consumption can improve health.

When skeptics are asked what it would take for mandatory sodium reductions to be enforced, the editorialists point out, the common response is "a clinical trial demonstrating that a reduction in dietary sodium caused a reduction in cardiovascular events." The new data, combined with other results, could be the proof needed to move recommendations toward requirements for sodium reduction in foods.

This month, the World Health Organization released new guidelines recommending reducing sodium intake to less than one teaspoon a day.

Each year, 8 million deaths worldwide are linked with poor diet, reports the WHO, and 1.9 million of those deaths can be attributed to high sodium intake.

So are we reaching an evidence-based tipping point for regulating sodium? Cardiologist Melissa Tracy, MD, a professor at Rush University in Chicago, told Medscape Cardiology, "Definitively, with capital letters, a shout-out, yes."

Health improvements in reducing sodium have been demonstrated in a number of studies, she said, and the current trial adds significant health benefits in stroke and mortality risk.

"When you start getting into double-digit reductions in stroke, double-digit reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events, major reduction in death," she said, "that's huge."

A Trans Fat, Food Dye Moment for Salt

Since the original Salt Substitute and Stroke Study, published in 2021 in The New England Journal of Medicine, Tracy says she has made a point of telling her patients about the benefits of salt substitutes, and she shows them the evidence.

Tracy keeps a container of salt substitute in her office to show an example of what it looks like and that it's inexpensive — almost the same cost as regular salt — and is easy to get with groceries.

The trial has also shown no adverse events from increasing potassium levels with salt substitutes, she pointed out.

"This has to be a health regulation," Tracy added, "just as we got rid of trans fats. Just as we're trying to get colors removed from foods. Patients who have risks, specifically high blood pressure, can't even eat out without their blood pressure shooting up."

Tracy recalls the conclusions of the authors of the 2021 study, who noted, "The magnitude of protection observed in this trial is similar to that assumed in a recent modeling study that estimated 365,000 strokes, 461,000 premature deaths, and 1,204,000 vascular events could be averted each year by the population-wide use of a salt substitute in China."

There's "huge value to this," Tracy said. "It’s lives saved. It's quality of life improvement."Still, many in the scientific and public health communities have argued the evidence has been insufficient to warrant new salt reduction strategies — including the use of government regulation to limit sodium intake.

Luke Laffin, MD, a cardiologist with the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, says he would welcome government restrictions on the amounts of sodium in foods, but he doesn't see that happening anytime soon.

While the findings from the subset of this trial add to the evidence, there are still some questions science hasn't answered yet, said Laffin, who is co-director of the Center for Blood Pressure Disorders.

There are always going to be concerns about what to substitute sodium with, he pointed out. "In this trial, it's potassium chloride. It does have potential dangers, particularly in people with kidney disease and other issues."

"I don't think we're at a point where the FDA would ever legislate this," he said, adding that the agency has supported voluntary reduction efforts.

Better Education About Food

The major sodium studies, including this latest one, have been conducted in countries outside the United States, Laffin pointed out. "You have to remember that Asian populations have a much higher amount of sodium in their diets than a typical North American population," he suggested.

China has the world's highest consumption of sodium, and the average daily sodium consumption among Chinese adults is more than two teaspoons of salt a day, even though Chinese Dietary Guidelines recommend well under a teaspoon a day.

"Is the effect going to be as prominent in a North American population? It's unknown," Laffin said.

"Salt reduction is the number one thing we should be talking about to our patients at high cardiovascular risk, particularly those with hypertension," he said. "But I think it would take more than [the new research findings] to legislate in the United States that manufacturers must have low sodium content."

Sodium is so ubiquitous in the US food supply that limiting it "would be very challenging to do. A typical piece of bread has sodium in it," Laffin added.

What can be done is better consumer education for making food choices, he said. In his practice, Laffin says he asks patients whether they track the amount of salt they are eating, and a common response he hears is that they don't add sodium from the saltshaker.

"But less than about 3% of the average person's daily sodium intake is from the saltshaker," he said. "It's mostly in the things we're eating, be it bread or cheeses or salad dressings." And "we know that anything from the deli counter is just jam-packed with sodium." Laffin says he reminds patients that reading labels is crucial in tracking salt consumption.

Also giving patients a quantifiable number to aim for with daily sodium intake, rather than instructing them to just watch their salt, will help, he says. They may think that by avoiding foods like chips and pizza, they are doing enough.

He says giving patients a bit of wiggle room may help them better adhere to a healthy plan.

The American Heart Association reports the ideal amount of sodium for at-risk patients is about half a teaspoon a day or 1500 mg, which is even lower than typical dietary guidelines, Laffin points out. "That's great if someone can achieve that, but 2300 mg is also a reasonable target because the difference in blood pressure reduction between 2300 and 1500 mg of sodium is only a few blood pressure points," he said. "So you can get more buy-in from patients if it's 2300 or less."

Other less well-known ways to reduce salt, Laffin said, include asking fast-food restaurants to make your meal without salt and then adding it yourself, if needed, or skipping salt altogether, he said. The no-salt choice is showing up on food delivery apps as well as in restaurants.

Source

Is This the Tipping Point to Slash Salt in Our Diet - Medscape

Bài viết liên quan